The New Science of Running Intervals

Interval training is a way of targeting specific physiological limits, but most runners never define which limit they’re trying to stress. As with most things, runners look at intervals in absolute pace terms. I want to run a 20min 5km, so I’m going to do reps faster 4min/km, and that will get me there.

So, I want to help you pick the right intervals for the job and introduce you to some new interval formations you’ve never considered.

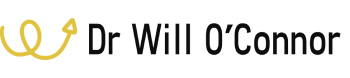

With the help of this amazing diagram from a 2024 paper titled “A narrative review exploring advances in interval training for endurance athletes.“

What I like about this paper is that rather than trying to pick a winning session, the researchers ended up with a much more useful output, which was this decision tree that starts with the important question.

What stimulus are you actually trying to create?

They frame everything around three determinants of endurance performance:

- Maximal aerobic energy production (so your aerobic capacity or base fitness),

- Anaerobic capacity (your ability to run above your lactate threshold)

- Gross efficiency. (How efficiently energy is turned into forward motion. i.e., running economy)

Every interval session biases one or more of these three components.

Traditionally, interval training emphasises keeping outputs smooth and metabolically stable. The Norwegian-style model is a good example of that: sustained work, controlled lactate, minimal spikes or variation.

What I found super interesting was that this paper looked at what happens when you keep the average workload the same across sessions but reshape how energy or effort is applied throughout the intervals.

They had four different types of intervals

- Fast starts, 4x {2min at 5km pace into 3min at 10km pace}

- Variable, 4x {3x 40sec above 5km pace, 60s at 10km pace}

- Micro threshold 3x {13x 10 – 30sec sprint with 15 – 30sec easy}

- And traditional, even-paced lactate threshold 5-15min intervals (~10km pace or LT2)

All with 2-3min recovery.

These sessions were described for cycling, so I’ve adapted the outputs for running. Where they say 5min mean max power, I’m using 3-5km race pace, FTP is equal to 10km race pace, and I believe the micro intervals need to be at least 30sec for running because runners can’t bust out 13x 10sec sprints like cyclists. So keep that in mind when you’re looking at this diagram. I suggest programming the workouts into your watch, so you always have them saved. Even something like a Garmin 55 will be sufficient if you’re new to GPS watches.

Anyway, across a large body of studies reviewed, the consistent finding was that varying effort distribution increases oxygen uptake and increases the total time spent near VO₂max or Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS), which is the slowest running speed you can run at to elicit your maximal aerobic capacity, typically around a 6-8min all out effort.

So when you compare fast-start intervals, variable-intensity long intervals, and micro-threshold intervals to traditional fixed-paced intervals, you get a more effective stimulus because you increase

- VO₂max

- pVO₂max (power or speed at VO₂max)

- Power/speed at 4 mmol·L⁻¹ lactate (which is a traditional LT2 measure)

- 20–40 min maximal power – i.e., 5 – 10km

But rather than saying that traditional lactate threshold sessions are dead, they argue that they shouldn’t be judged successful by the same VO2max-specific criteria.

Instead, their success lies in

- Improvements in fractional utilisation of VO₂max, essentially how fast your marathon pace is relative to your VO2max.

- Increased power/speed at lactate threshold.

- Improved sustainable aerobic output, your aerobic base.

That’s why FTP, or “threshold”, sits as a separate branch in the decision tree. It’s a different outcome target rather than a less good version of interval training.

So, what are my recommendations, and how can you apply this information in your training?

First, review this diagram and try some intervals that match your weaknesses to see how you respond. (Remember my adjustments for converting the outputs from cycling to running.)

For most runners, the variable interval formats make the most sense early in a half or full marathon training cycle, where you can push VO2max and running economy up before shifting to a more traditional endurance training style where you’re trying to build the fractional utilisation component.

But if you’re targeting a 5K–10K build, where anaerobic power and neuromuscular qualities are more directly limiting. Personally, I’ve found the fast starts or declining exercise intensity (DEC) intervals, as they’re scientifically defined, where you have 2min at 5km pace into 3min at 10km pace with 3min recovery to be extremely successful for 10km prep. I’ve used them, I have them in my 10km plans, and they worked great last year with a runner who placed an unexpected 4th at our national 10km champs.

It’s important to note that the further along the neuromuscular stimulus scale you go, the more taxing the session is, regardless of what your watch tells you, so I’d only recommend 1-2 per week, and I’d be very cautious if you’re injury prone. But if you wanted an extreme training experiment, cyclists have used the micro thresholds, so the 20-30s sprints, 5x per week for the two weeks leading into an event to great effect. But I am not recommending that. But do email if you try it.

(FYI. Here’s a paper on the effects of 7 consecutive days of HIIT. Can you imagine doing that!)

The key takeaway is that your interval training needs to be viewed from the perspective of “what stimulus am I trying to achieve, rather than how fast am I trying to run”. Or as I always say, let your “physiology dictate your finish time”

Watch the full video below.