The long run is a staple of any ultramarathon training plan, but there is also the “longest run”. But what is long?

The long run is a staple of any ultramarathon training plan, but there is also the “longest run”. The longest run is “the big one” that is meant to test your physical and mental stamina leading into your target event. However, there remains a debate over the duration of either run―what is long? Within this article, I attempted to throw some science at the concept to see if I could figure out some appropriate recommendations for runners of all abilities. We have two reasons to complete a “long run” during ultramarathon training.

- Physical

- Mental

Physical

Physical is the obvious reason for completing a long run, but it is also important to be mentally prepared for the duration you are going to spend on your feet. It is also necessary to find out how your equipment and nutrition are going to work over ultra long durations. Blisters, chafing and gastrointestinal issues can be the undoing of anyone’s ultra ambitions.

One question that has never been definitely answered is how long should your long run be?

First, let’s look at fitness. There is an optimal intensity for endurance training, which is usually referred to as “zone 2”. You want to be running fast enough that there is a stress response within your muscle, but you don’t want to be running too fast that the stress is overwhelming and you are unable to recover from it (i.e., zones 3, 4, and 5).

There is enough evidence in the literature to verify that zone 2 is the optimal training zone. Zone 2 is equivalent to 75–85% VO2max, 80–85% Max HR, or 10–20% slower than your average marathon pace. VO2max or “maximal volume of oxygen uptake” is a scientific term used to reference an individuals ability to utilise oxygen while exercising. The higher your VO2max, the more oxygen you are able to use to generate the energy required to run i.e., the fitter you are. If we can agree that zone 2 is the optimal training intensity for endurance, we then need to determine what is the limit of time someone can run at zone 2.

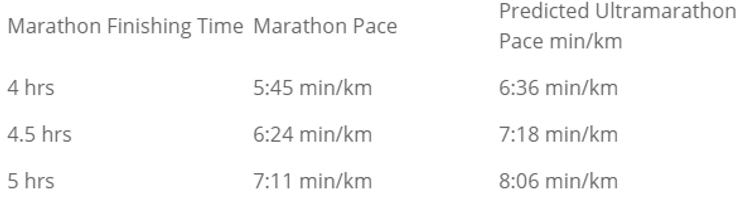

According to global statistics, the average marathon time is 4.5 hrs, equating to an average pace of 6:24 min/km. From laboratory tests, we know that marathons are typically completed at 70–75% VO2max.

Ultramarathons, on the other hand, are typically run at 65% VO2max with a drift up to 70% VO2max due to muscular fatigue and loss of efficiency. Efficiency relates to the amount of oxygen required to run at a designated speed. Less efficient runners require more oxygen to run at a certain speed. As your running form breaks down over the course of an ultramarathon you become less efficient.

The difference in sustainable intensity between a marathon and ultramarathon means you’ll be running, on average, 14.3% slower than your average marathon pace. You can calculate your predicted ultramarathon pace by multiplying your average marathon running pace by 1.143. Note, though, that this not a race predictor, it is just a predictor of your “running” pace. Because it’s an ultramarathon there’ll be times when you are walking and stopped at aid stations all of which affect your overall average pace at the finish.

An issue arises when the pace at which you are predicted to “run” can’t actually elicit 65% VO2max because you’re not actually running. When this is the case, you’ll gain a better “return on investment” by running faster for a shorter duration.

Remember, the fitter you are the faster you can run. If you have a higher VO2max not only can you run faster, but you’ll also be able to sustain your predicted pace for longer. Fitness is the number one goal. However, this is not to say the super fit runner should go out and run for as long as they possibly can. For both fast and slow runners, there is a point of diminishing returns. The fast runner can run too fast for too long and induce too much fatigue beyond what they can recover from. Conversely, the slow runner can run too slow to not gain any positive stress response.

OK, so how long?

As mentioned in the introduction, we complete long runs for two reasons: physical and mental. Your longest run should not be regarded as a session that will increase your fitness because it is not wise to think you can gain a huge boost in fitness by doing one run that’s 2–3hrs longer than your normal long run. By the same logic, you could simply go out and run as long possible as often as possible and get infinitely fitter. Unfortunately, we need to recover from these physically demanding sessions, and the less fit you are the longer it will take you to recover.

Without adequate recovery from your super long training sessions, you’ll go backwards rather than forwards, and we’ve all been there! Knowing that your longest run is not about physical fitness and is predominantly for mental experience, what is the appropriate duration for each runner? There are a lot of theories out there such as two-thirds of your estimated race time, at least 50 km for a 100 km, no more than 3 hrs, etc. However, these theories and the many others are founded on an experience of n = 1, rather than science.

What’s My Limit?

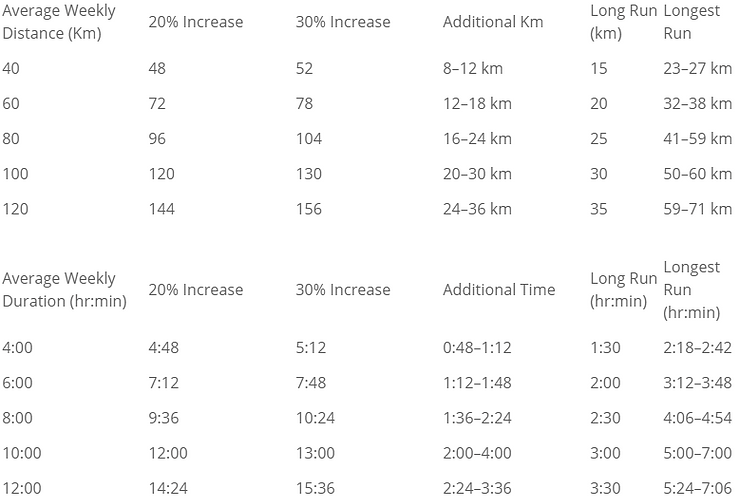

If there is a limited to how long you should run, what is it? Luckily, a number of studies have looked at the training threshold that results in injury. Research suggests the threshold for injury is roughly a 20–30% increase in your weekly training load. Based on this threshold you can do a rough calculation of your weekly training load using your weekly distance, duration or you can use a more complex system such as training impulse (TRIMP), training stress score (TSS) or Strava’s relative effort.

Using the 20–30% increase recommendation I’ve compiled two reference tables based on the average weekly training distances and durations of most trail runners. Each table shows the average weekly training volumes, the weekly training volumes for 20% and 30% increases, a summary of the additional weekly training, recommended long run distance based on training volume and longest run recommendation calculated as the additional training volume allowance based off the 20–30% rule plus the recommended long run distance/duration.

When using the table, it is important to consider two of the key points raised: 1. Your long run is for fitness, and if you struggle to “run” for the majority of your long run, you’ll be better off reducing the duration/distance to get a better training response. 2. Your longest run is not for fitness, it is used to familiarise yourself with your experiences on race day, so try to replicate your nutrition, equipment, and course profile.

To summarise, rather than looking at the duration of your event and trying to figure out how long you need to run, research shows the length of your longest run, should be based on your previous training volume to maximise your benefits from the run and minimise your chance of injury.